What is it about cinema that make this medium so susceptible to reverential paeans to itself? What is it about celluloid spools, magnetic tapes, LaserDiscs, or the hyaline crispness of contemporary digital image that is able to continually hypnotize and afflict generations after generations with a deeply dysfunctional affection known as cinephilia? For many, the sparest of means — sun-splashed image from a projector radiating in a dark room — a first encounter, and unlikely the last, can hold sway a lifetime of cinephilic obsession akin to the very seismic, flattening, and all-conquering effect of a first love.

The 2nd year of SeaShorts film festival begins brightly by turning obsessive reflection from subject to project. Taking place in the timeworn townscape of Georgetown, Penang, heritage spaces with its chaotic ramshackle appeal captivate the city for five days by playing host to a festival dedicated to showcasing the best of Southeast Asian short films. Perhaps ever-appropriately, the opening program, titled “My Student Film”, takes to task the physiological, if not metaphysical, preoccupation of Southeast Asian filmmakers. Through laborious curatorial work involving the collective effort of the entire region, 7 film school theses of well-established filmmakers the likes of Garin Nugroho, Aditya Assarat, Dain Said, and Anthony Chen are given a new lease of life, some revived from their moldy VHS tapes by Asian Film Archive. It’s a program that retreats into the past, but it’s not strictly nostalgic. The very tracery of such a series chronicles and contextualizes the developing sensibilities of these directors when they were young, discovering not the unraveling of mysteries and dramas of their new works, but their very genesis.

There are many outstanding films in the program, two of which concern cinema, one more spiritually while the other more explicitly. Garin Nugroho’s Gerbong 1, 2, 3, falls into the former category. Set in and around the railway stations in Indonesia, 2 men and a woman converse about illusion and reality, independence and American presence, life and death, and cinema and meaning. For a student work, Nugroho exhibits the very measure of a deft auteur-in-the-making, weaving intricate formalistic play with photoroman flourishes that wouldn’t seem out of place in a Godardian work. But what is more impressive in Gerbong is the trigger of an archaeological element of cinema going back to the 19th century. One of the earliest forward-moving shots in the history of cinema — Passage d’un tunnel en chemin de fer pris de l’avant de la locomotive — essentially a unidirectional shot taken from a moving locomotive train gliding across the tracks heading towards the Gare de Saint-Clair, filmed by the Lumière brothers in Lyon in 1898, is astonishingly revived again in Indonesia after close to a century.

If nothing more than a metafilmic nod, Nugroho evokes this historical lineage with the line “Still remember the moments before the last train wagon went by?” If this further concretizes Lumières as a spiritual progenitor to Gerbong, Nugroho flatly challenges it in the next shot. At one point in the film, Nugroho slow-cranks the camera mounted on the train in an unbroken 360-degree turn, upending visually and historically any canonical overdetermination attempted on the film, leaving the young Indonesian man suspended in the skies as he runs after the train. Nugroho’s usage of slow-advancing train shots are also more sophisticated than what was available in the past. Narrative voiceover infiltrates tracking train shots, the tone constantly hovering in between fogs of illusion and reality, infusing the short with an opiate-like quality that perhaps Nugroho wants the cinema of Indonesia to break away from, hinting at some point the pervasive influence of American politics and media in the local landscape, evidenced when he intermixes local ink sketches with a photomontage of Ronald Reagan in competing sequences.

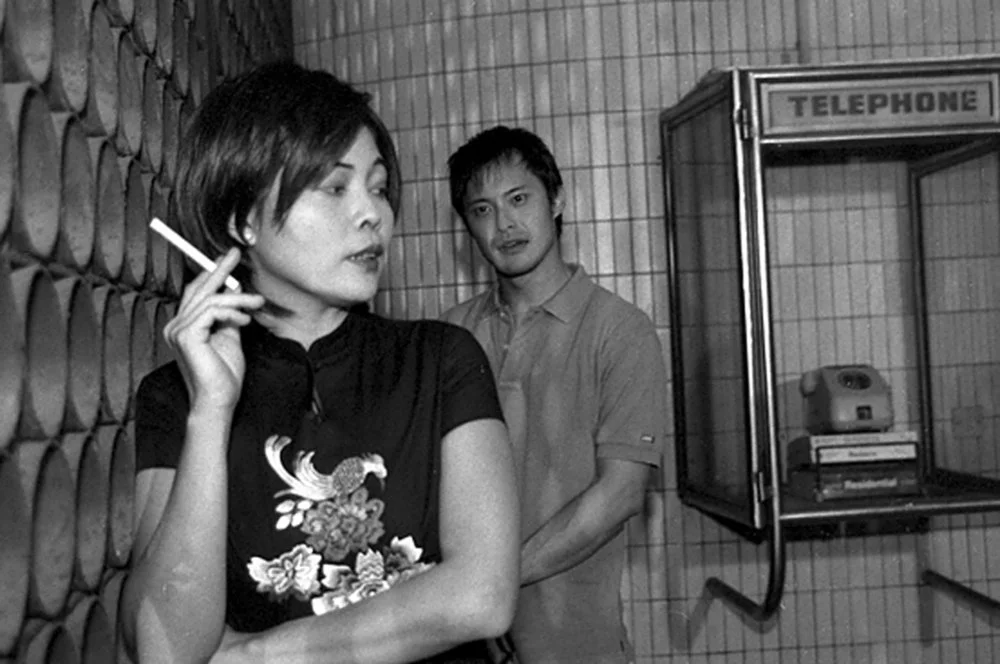

In the case of Anthony Chen’s G-23, the quintessence of youthful filmmaking’s sheer exaltation is at its full flourish. Falling into the latter category of more explicit cinephilic evocations, G-23 exhibits a young filmmaker’s enthusiastic exuberance for the medium. Made when Anthony was just 19, the short chronicles the story of three idiosyncratic city dwellers: a young Indian girl, an elderly man, and a middle-aged lady from the perspective of a lone ticket usher. It’s an array of social misfits who might very well wander into Tsai Ming Liang’s filmmography, particularly that of Goodbye, Dragon Inn. While Anthony’s various cinematic gestures aren’t coy in its awareness — the middle-aged lady is one detail away from doing a full Brigette Lin in Wong Kar Wai’s Chungking Express, contemplating over a lychee can instead of a pineapple can — the film, despite its effusive homage, remains central to the very pressure-cooker environment that typifies the megalopolis, interweaving the phenomenon of urbanite disaffection into a morosely funny Singaporean tale.

These films represent touchstones in Southeast Asian film history. Anthony Chen would go on to make Ilo Ilo, and Garin Nugroho Opera Jawa. In that essence this series exhibits the nascent talent of the region already in the making. Not once do these works succumb to the temptation of vacuous pastiche, or worse, awed mimicry out of complete deference. Instead, there’s enough social and historical import palpable in the films in and of itself. With the sparest of means, the SeaShorts film festival has organized a program that captures the cinematic grace of the region, giving form to a collective dream where a dark light in an empty hall can create an international, intergenerational, intertextual, and intraregional echo chamber of cinema and longing in Southeast Asia.

Wei Jie Lim is a freelance filmmaker, screenwriter, programmer, writer, and photographer based in Malaysia and Southeast Asia. He is a graduate of the Tisch School of Arts, NYU with a double major in Film/TV Production and Philosophy.